May has been good to me.

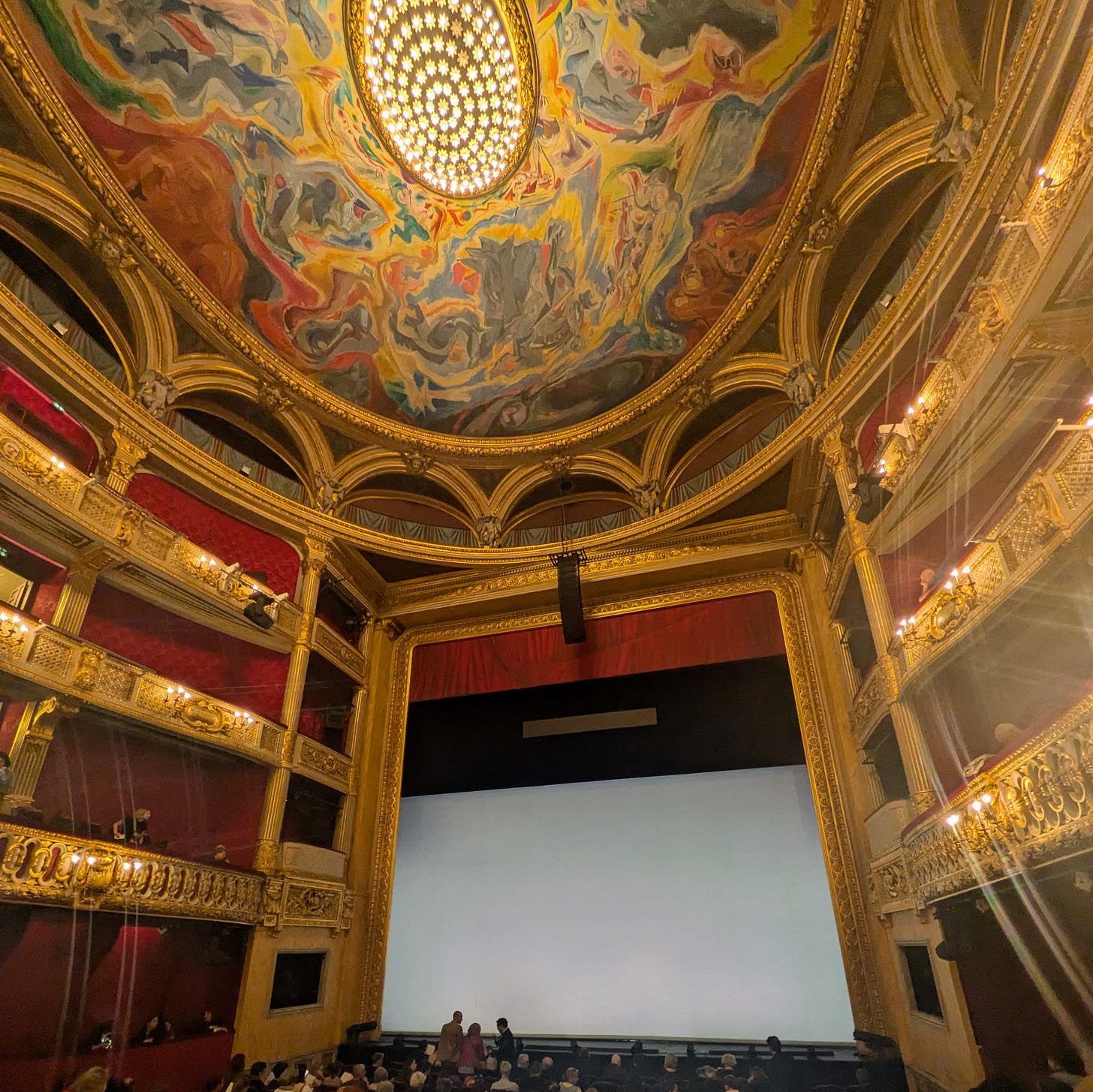

Last night I saw Georges Feydeau’s 1894 vaudeville play L’Hôtel du libre échange at Odéon. I was amazed at how little it had aged. The actors were absolutely brilliant, and the experience of laughing hysterically alongside others at the theater was magical.

In other news, we’ve begun rehearsals for our upcoming recital, Rêveurs, June 13th and 15th at Studio l’Accord Parfait. Program and booking details coming soon!

May’s long weekends have also allowed me to treat myself to more reading than usual. This week I’d like to discuss Marilynne Robinson’s 1980 novel Housekeeping.

Housekeeping is about two sisters who are abandoned by their mother. Set in the fictional town of Fingerbone, Idaho, Ruth and Lucille are first left with their grandmother, then with their grandmother’s sisters-in-law, and finally with their aunt Sylvie, an extravagant vagabond with a mysterious past. The rural landscape plays a major role in the story, both figuratively and literally. A rail bridge over an enormous lake serves as the town’s connection to the outside world, be it to distant cities or to the unknown territory of death.

I had originally picked up this novel because of its various water-related scenes, something I’m working on in my own writing. But what ended up intriguing me the most was its pacing and point of view.

The pace of Housekeeping led me to wonder: do novels, like music, have a tempo?

In English poetry, one is to notice rhythm in cadence and meter, but these are less often observed in prose. A long work of prose needs to have some kind of engine propelling the reader forward, but many novelists think of this as a question of plot. While reading Housekeeping, though, I began to realize that the rhythm of language counted just as much. I couldn’t help but feel like Robinson’s novel had a slow yet steady tempo, something like adagio, that determined the speed at which I turned its pages.

Tempo literally means “time” in Italian, and in many scores of music, it is indicated with words like presto or largo and/or a “beats per minute” number. This number defines a unit of time within a piece of music, a beat, in relation to one of our ordinary units of time, a minute. A beat in a piece of music is essentially like a second in a piece of life. Different tempo markings could therefore make the same three-page score last thirty seconds or three minutes: it all depends on the rate at which a beat is to occur.

If you aren’t a musician and none of this speaks to you, I ask more simply: what is responsible for the speed at which we read the language of a novel?

Let’s take a look at a beautiful passage in Housekeeping:

I hated waiting. If I had one particular complaint, it was that my life seemed composed entirely of expectation. I expected—an arrival, an explanation, an apology. There had never been one, a fact I could have accepted, were it not true that, just when I had got used to the limits and dimensions of one moment, I was expelled into the next and made to wonder again if any shapes hid in its shadows.

—Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping, Chapter 8

Robinson begins with a simple three-word sentence before expanding into a complex sentence with the subordinator “if.” In this way, the text modulates (to borrow another musical term) from the declarative to the conditional. It then returns to the first simple structure with “I expected,” but adds a list of direct objects separated by an em dash, as though the sentence were an elongated echo of the first. This is followed by a second complex sentence with a more complicated conditional.

Structurally, then, the passage creates a pattern of alternating simple and complex sentences that snowball in length. Visually, I imagine lungs breathing in and out at different speeds, or an accordion expanding and retracting: short / long / longer short / longer long.

Fittingly, the content of this passage focuses on waiting, a state that makes time feel very slow. Waiting is written into the language as the reader begins with a quick, accessible subject-verb-object before the promise of this simplicity vanishes into a tangle of subordinates that slows them down. Robinson creates a thirst for clarity that gives the reader the gift of intricacy: a readable literary novel.

Thinking about terms from other artistic mediums is not only fun but helpful, much in the way French has helped me become a better writer of English (I think…). While I like to write first drafts organically, in revisions, I’m planning to experiment with grammar to fix the rhythms of stubborn passages. I may also ask myself what tempo I’m in: am I dragging behind the beat?

I’ll hold my comments on Housekeeping’s fascinating point of view to not spoil the novel. But if you’ve read, I’d love to discuss.

à la prochaine !

Rachel